By: Paula Sengupta

Abstract

LIVING A DARK NIGHT

For twenty months now, India is living a dark night. Dawn never breaks … the night only gets darker. In the summer of 2020, the country witnessed the exodus of millions who form the backbone of the nation’s economy, making journeys of the scale that India had not seen since her borders were drawn. Journeys to find shelter and escape starvation, away from the big cities that shunned so many overnight.

Even as the first rays of the sun shone dimly through the dark, a black night descended in the spring of this year. While some made hay, a dreaded, unbridled beast unleashed its fury on an unsuspecting people. With unspeakable stealth, the beast gained ground, now striking young and old alike. Its victims gasped for breath, thirsting for the very air that every living creature on this planet is entitled to breathe. And when they gasped no more, their pyres burnt on sidewalks, in parking lots, and in crematoriums where flames did not die down in weeks. Even in death, there was no dignity.

And through this, there are those that provide succour to the suffering … medical facilities, of course, but also places of worship, citadels of education, civic buildings, and citizens. All struggling to rise to the occasion and help India heal.

In the wake of the deadly second wave of the pandemic, I sent out a call to students and fellow educators and artists to rise and raise their voices, harkening back to the original role of Printmaking, the most democratic of all art-making processes. Since the 18th century, European artists such as William Hogarth, Francisco Goya, Honore Daumier, William Blake, and later the German Expressionists invoked the medium of printmaking to register human anguish. But I will cite closer to home the inimitable artist quartet Zainul Abedin, Qamrul Hasan, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya and Somnath Hore as our points of reference. This quartet, realising the potential of printmaking as a medium for the masses, fiercely used the burin and the bully to depict the wounds of Hungry Bengal and arouse the patriotic fervour of an enslaved people. Agitating against the British ‘scorched earth’ policy implemented in the Chittagong countryside during the Second World War, these artists moved from village to village as volunteer workers, sharing the suffering and poverty of famine-stricken Bengal. Led by Chittaprosad, printmaking assumed a new role as an instrument of protest.

It would not be incorrect to say that the anguish that India is suffering today has not been seen since the Bengal Famine of 1943 or the Partition of 1947. As creators, ‘Living a Dark Night’ invited artists to come together to hear this anguish and register it for posterity, lest history forgets. Artists have responded in overwhelming numbers, returning printmaking to its original democratic role.

‘Living a Dark Night’ is now ready to go on exhibition with the following chapters:

The Onslaught

Death & Survival

Lockdown

The Exodus

The Domestic Space

Anguish & Anxiety

The Healer

As curator, this essay will feature the ‘Living a Dark Night’ project with selected images, in the context of the time that it attempts to freeze in public memory.

Keywords: Lockdown, migration, anxiety, representation, printmaking, public memory

LIVING A DARK NIGHT

Articulating The Artist’s Voice

The Covid-19 pandemic first arrived at India’s doorstep in January 2020, with the country going into a sudden, unplanned and draconian lockdown on 25 March the same year. Amongst other disasters, in the blazing summer of 2020, the country witnessed the exodus of millions who form the backbone of the nation’s economy, making long and perilous journeys that India had not seen since her borders were drawn. Journeys undertaken to find shelter and escape starvation, away from the big cities that shunned so many overnight.

On 10 June, India’s recoveries exceeded active cases. Daily cases peaked mid-September with over 90,000 cases reported per day, dropping to below 15,000 in January 2021. The country grew complacent, imagining that India had beaten Covid. Governments turned their attention from managing the pandemic to winning elections and hosting mammoth religious congregations, throwing caution to the winds.

Even as the first rays of the sun shone dimly through the dark, a black night descended in the spring of 2021. While some made hay, a dreaded, unbridled beast unleashed its fury on an unsuspecting people. With unspeakable stealth, the beast gained ground, now striking young and old alike. Its victims gasped for breath, thirsting for the very air that every living creature on this planet is entitled to breathe. And when they gasped no more, their pyres burnt on sidewalks, in parking lots, and in crematoriums where flames did not die down in weeks. Even in death, there was no dignity. The night only got darker …, dawn never broke.

Through this, there were those that provided succour to the suffering, not only medical facilities of course, but also places of worship, citadels of education, civic buildings, and citizens. All struggled to rise to the occasion and help India heal.

Living a Dark Night was born in the wake of the deadly second wave of the pandemic. The Kala Chaupal Trust, Gurgaon and I sent out a call to students, fellow educators and artists to rise and raise their voices, harkening back to the original role of printmaking, the most democratic of all art-making processes. Since the 18th century, European artists such as William Hogarth, Francisco Goya, Honore Daumier, William Blake, and later the German Expressionists invoked the medium of printmaking to register human anguish.

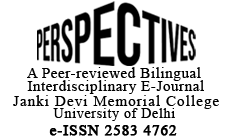

Käthe Kollwitz, The Mothers, Woodcut, 1922, 47.8 x 64.9 cms

Similar histories exist in the backdrop of the Chinese Communist Revolution or in protest movements in Latin America.

Li Hua, Celebrate the Surrender of Japan and the Victory of China,

Woodcut, 1946, 20 X 27 cms

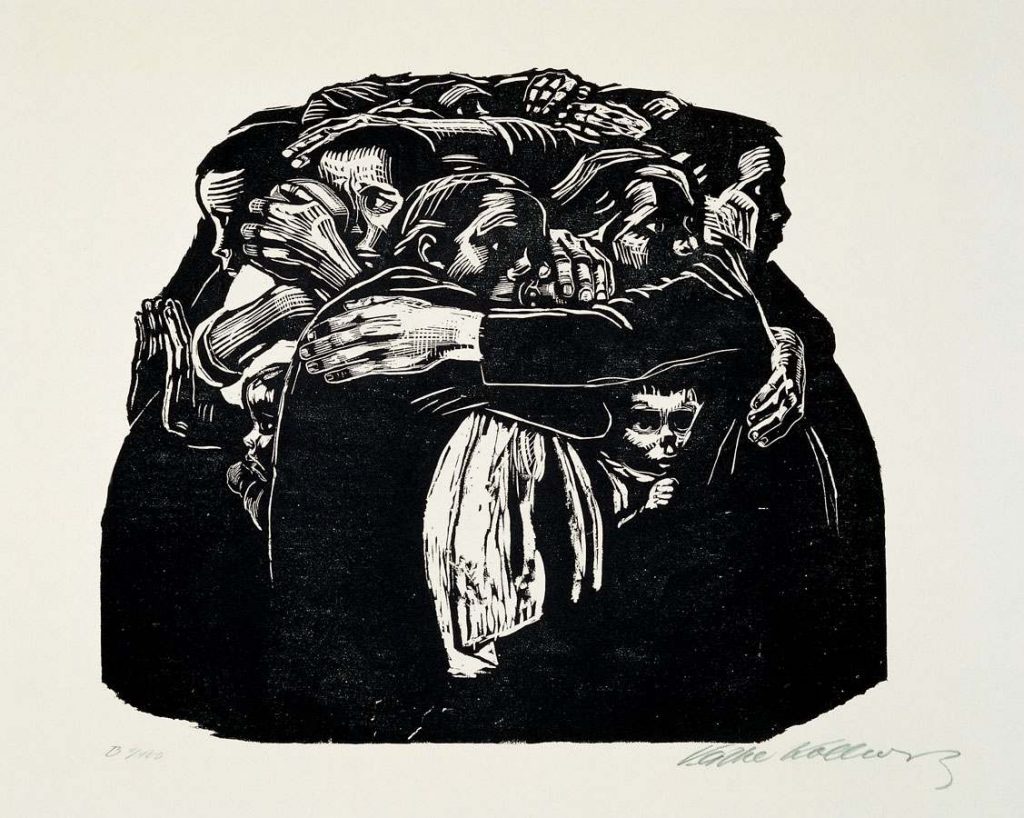

Xavier Guerrero, Oil refinery workers, Woodcut, 1924, 18 x 12.6 cms

But I will cite closer to home, the inimitable artist quartet Zainul Abedin, Qamrul Hasan, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya and Somnath Hore as our points of reference.

Chittaprosad Bhattacharya, Orphans, Linocut, 1950s

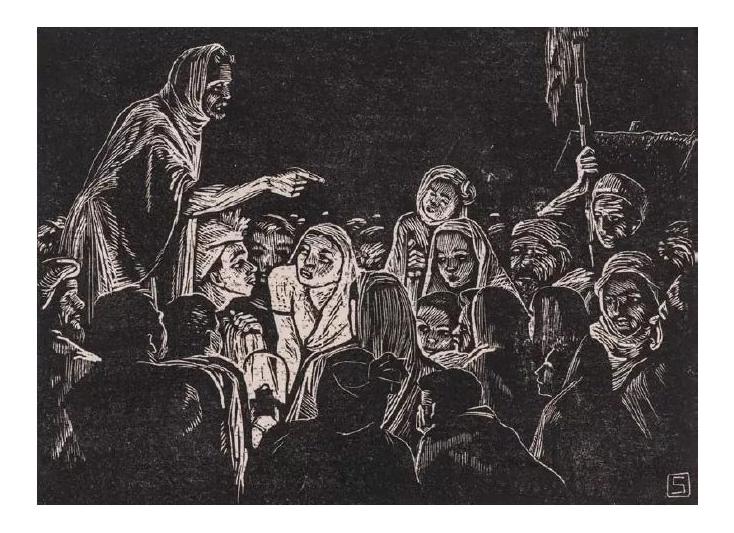

Somnath Hore, Night Meeting, Wood engraving, 1955

This quartet, realising the potential of printmaking as a medium for the masses, fiercely used the burin and the bully to depict the wounds of Hungry Bengal and arouse the patriotic fervour of an enslaved people. Agitating against the British ‘scorched earth’ policy implemented in the Chittagong countryside during the Second World War, these artists moved from village to village as volunteer workers, sharing the suffering and poverty of famine-stricken Bengal. Led by Chittaprosad, printmaking assumed a new role as an instrument of protest.

For 20 months now, India has been living a dark night, from which we are yet to awake. It would be correct to say that the anguish that India is suffering today has not been seen since the Bengal Famine of 1943 or the Partition of 1947. Along with every other sector, artists too have suffered an existential crisis, with avenues and livelihoods wearing thin with every passing day.

As creators, Living a Dark Night invited artists to come together to hear this anguish and register it for posterity, lest history forgets. The works in this initiative encapsulate a time of despair and anxiety, when artists withdrew into the studio as the only space of refuge. Executed in a space of isolation, these prints look from deep within to the spectre without; but also from darkness to light.

Artists responded in large numbers, some expressing solidarity even from overseas. Submission deadlines were extended many times, with artists facing paucity of materials, lack of mobility, erratic courier schedules, all brought on by interminable lockdowns, yet keen to join hands with us. Even as we prepared to launch the initiative virtually, prints continued to trickle in.

Living a Dark Night is about the power of the print, the bare brutality of black against white referenced again and again by artists since time immemorial, about standing together as only printmakers can, about returning printmaking to its original democratic role. Even as we in India await a possible third wave, Living a Dark Night stands as a stark reminder of our folly.

The Onslaught In April 2021, India entered perhaps her longest and darkest night since Partition. The virus that we had imagined tamed, swept across an unsuspecting nation, catching both its people and its administration unawares. With unprecedented vengeance, it struck both young and old alike, leaving them gasping for breath, where none was to be found. Not a home, not a family remained untouched

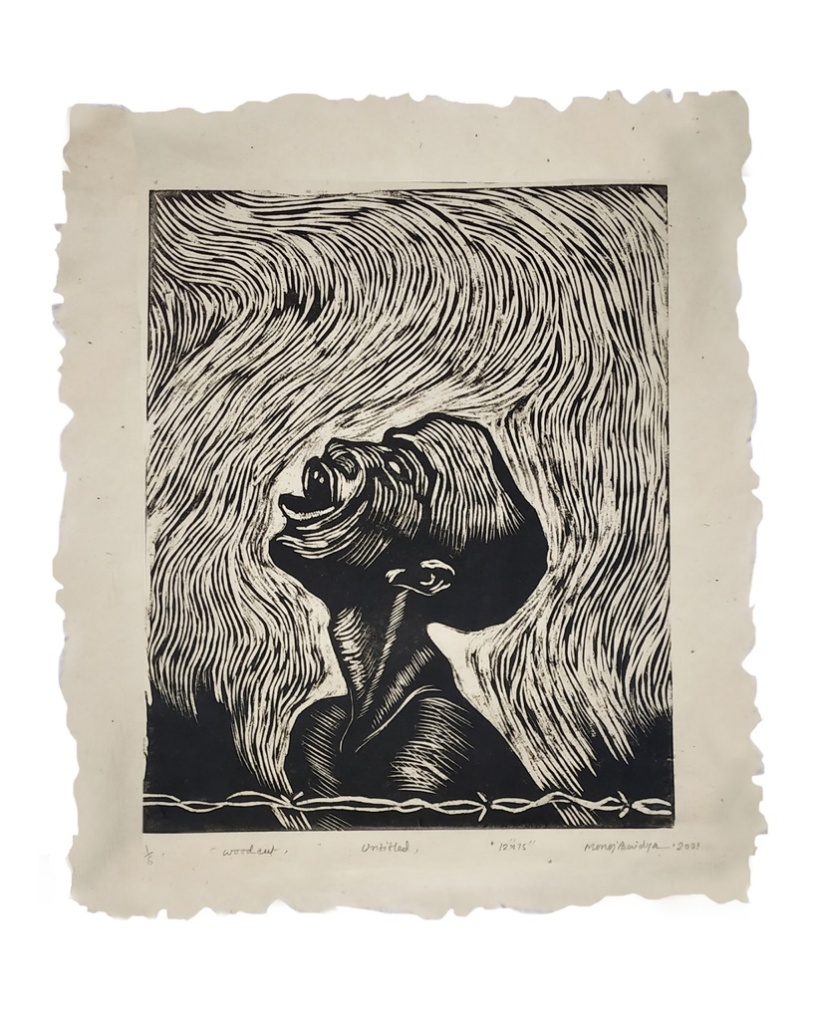

Khokan Giri, Pain of Heart, woodcut, 30.48 x 38.1 cms

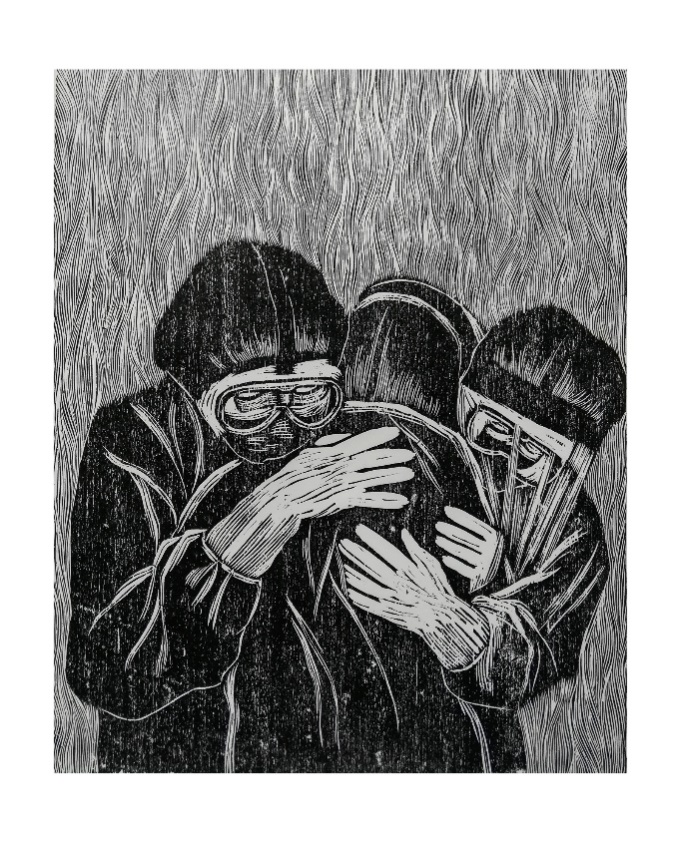

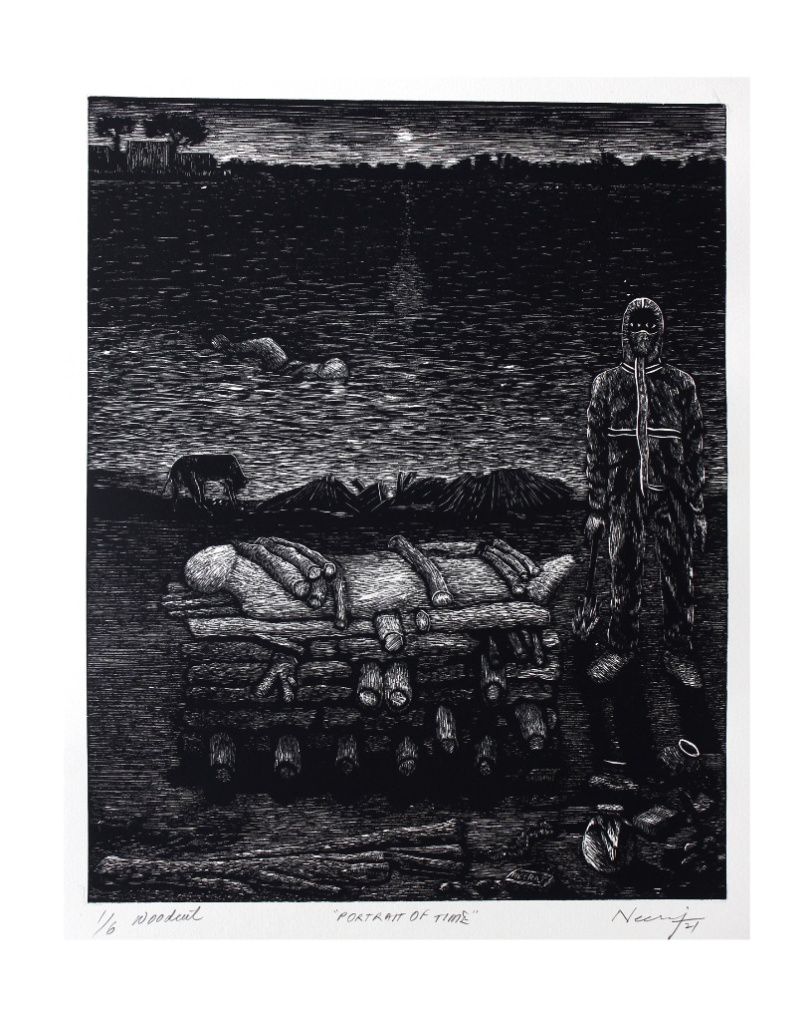

Death and Succour

The dark night engulfed all in its long shadow. Shrouds became the order of the day, both for the living and for the dead. India’s skies turned crimson as pyres burnt around the clock, the stench of death permeating everywhere. The teeming metropolises of India were now citadels of death and decay.

As quarantine became the order of the day, suffering and dying became a solitary act. Yet, succour was not shortcoming from both organised and unorganised sectors. Humanity came together in the hope of a new dawn.

Neeraj Singh Khandka, Portrait of Time, woodcut, 30.48 x 38.1 cms

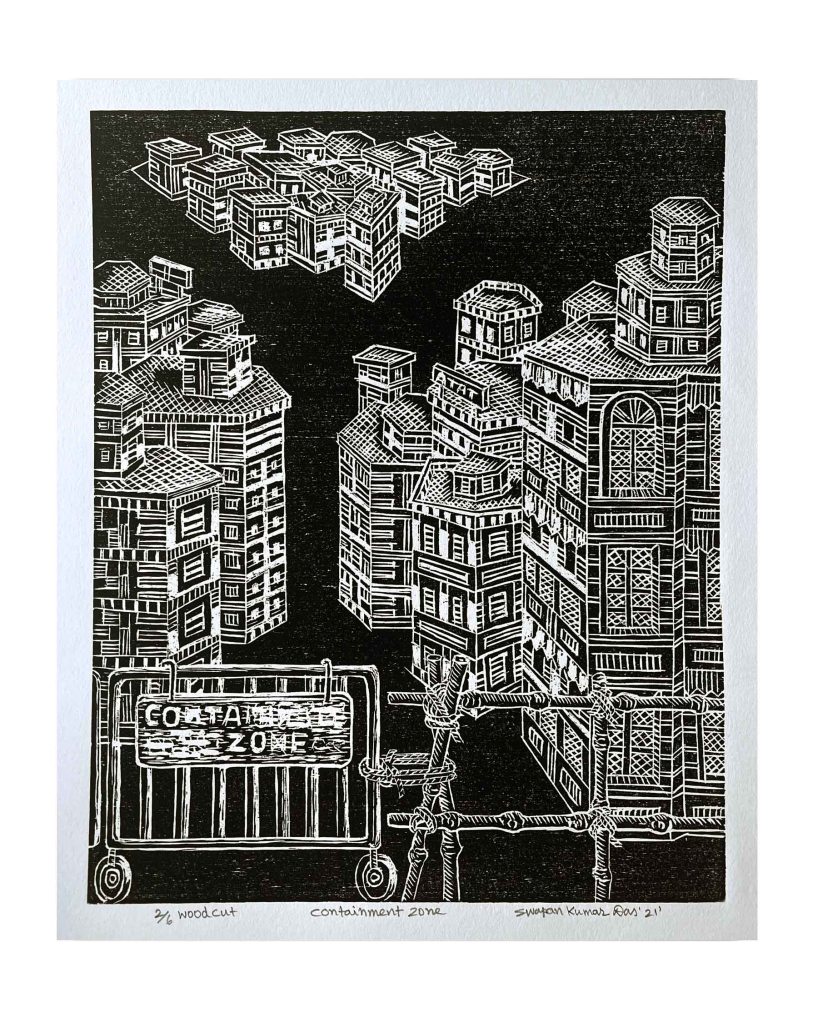

Locked and Down

In the shadow of night, cities that never slept, came to a grinding halt. Skyscrapers that trembled as commuter trains screeched past, froze in mid-air. Neighbours ceased to meet as neighbourhoods became ‘contained’. Chimneys spewed their last cloud of smoke as factories shut shop across the country. Human beings retreated into contained capsules in an attempt to ‘stay safe’, leading surreal virtual lives, looking outside with anxiety, fear and distrust.

Swapan Kumar Das, Containment Zone, woodcut, 30.48 x 38.1 cms

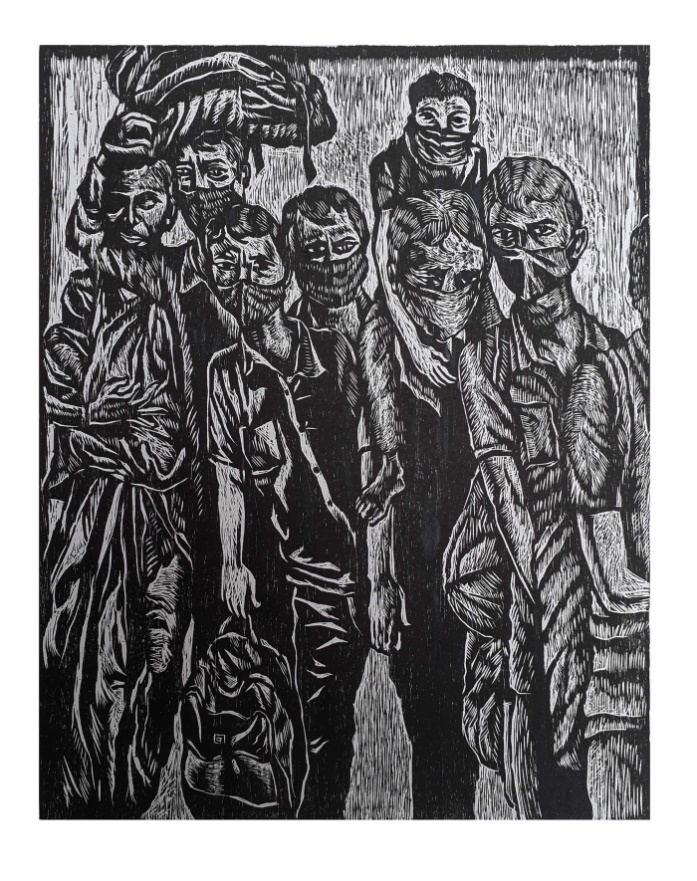

The Exodus

As India locked down on 25 March 2020, livelihoods dried up. As the Indian summer gained momentum, an estimated 40 million internal migrant workers, largely in the informal economy that forms the nation’s backbone, were displaced. In a move that was entirely unanticipated, these millions traversed thousands of miles on foot, with neither food nor water, carrying their young and old, their meagre possessions on their person, in a desperate bid to reach the villages that they called ‘home’.

It was a march of migrants that shook the world.

It was also the march that took the pandemic to the remotest corners of India and beyond even her borders.

Susanta Pal, Procession, woodcut, 30.48 x 38.1 cms

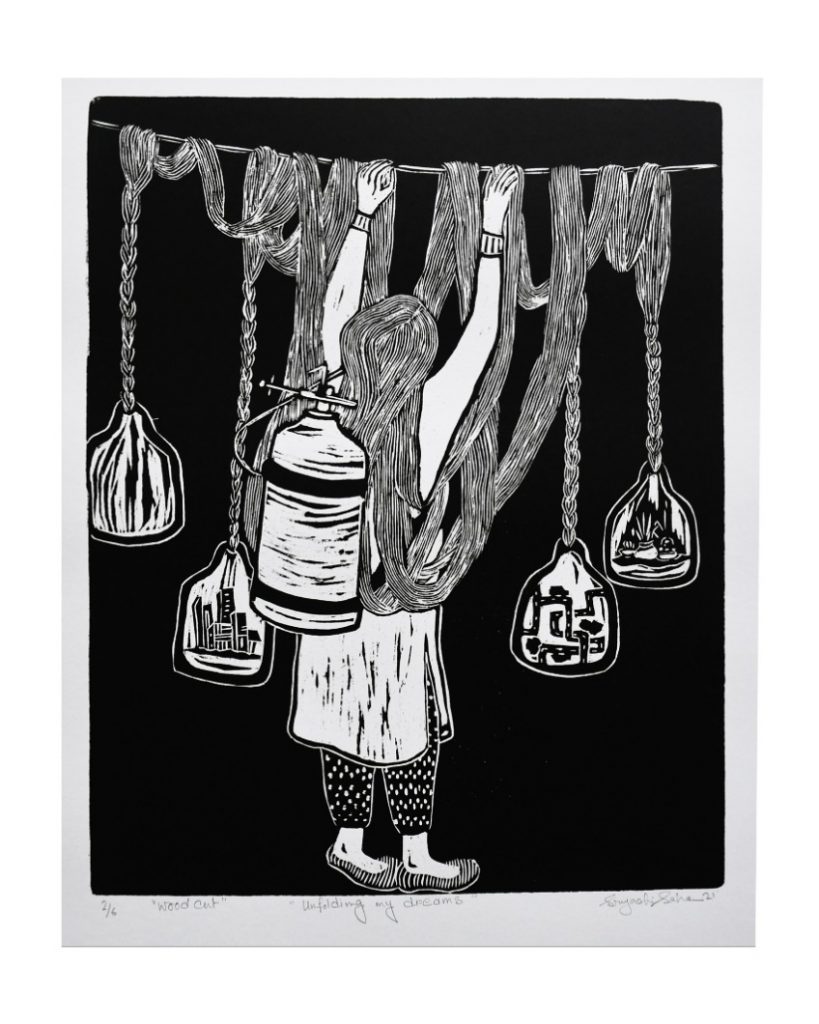

The Domestic Space

The home now became the primary space of occupancy, out of which people both lived and worked. This created new equations, anxieties and tensions within the domestic space, as people packed in like sardines. The brunt of this was borne by women, with the traditional role of homemaker emerged as doubly challenging. Even as the lives of children, office-goers, and the elderly became increasingly dysfunctional in the pandemic, women performed with enhanced efficiency, keeping home and hearth together through a time that was both endless and trying.

Sreyashi Saha, Unfolding my Dreams, woodcut, 30.48 x 38.1 cms

Anguish and Anxiety

In this long, dark night, portraits of anguish and anxiety stand testimony to the nightmare that we are living. Our masked visage no longer allows us to smile. Our isolation gives us no cause to smile. A glance in the mirror tells us that nearly two years have passed us by. Our desolate homes are mirrors of our desolate lives. Our screams of despair echo within the four walls that we inhabit or through ghost towns that may never rise again from the ashes.