Abstract

This paper attempts to offer a narrative where kaali-peelis — often associated with a certain kind of private space and middle-class privilege in the city — are a microcosm of the migrant narrative of Bombay which lies at the intersection of several kinds of access and narratives of the city. Their dwindling numbers are symbolic of a fading nostalgia and of the shifting identities and access points that add to the narrative of Bombay. This paper will attempt to capture the narrative produced by an enforced pause on the city following the nationwide lockdown from March 2020, and how it is reflected in the context of Bombay’s iconic public-private transport.

Keeping the taxi, and its representation on Instagram by @thegreaterbombay as the rhetoric, this paper will explore the migrant question of claiming the Bombay identity in the context of the city’s specific history with migrant populations. This is further complicated through the lack of access to private space and the legitimacy of claiming the Bombay identity, while engaging with the space primarily through labour.

This migrant narrative of the legitimate claims to the Bombay identity is disrupted by the national lockdown, and the Bandra Station incident on April 14, 2020. The paper will use this incident to locate the movements of the migrant identity and its narrativising of the Bombay space.

Keywords: Private space, privilege, access points, social media, migrant populations, Bombay

List of abbreviations

SMS: Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti

SS: Shiv Sena

MNS: Maharashtra Navnirman Sena

MMR: Mumbai Metropolitan Region

BMC: Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation

RHA: Rental Housing Authority

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank @thegreaterbombay for their insightful interviews, fun conversation and their permission to use the screenshots of their profile and posts for this paper. I would also like to thank @mumbaipaused for their incredibly deep engagement with Bombay, and their profile name, which inspired this paper’s title.

1. Introduction

Bombay, it can be argued, is a city of and by migrant populations. Before the British occupation of the Salsette Islands, vis-à-vis the marriage of Charles II and Princess Catherine (Cadell and Page 1958), the seven islands were only recorded in history as marshy islands, with a host of tropical diseases, and no economic or strategic value to mention. Some areas that we now understand as Bombay have archaeological remnants that Naresh Fernandes, in his book City Adrift, refers to as the ‘detritus of two millennia [sic] just a train ride away’ (Fernandes 2013). However, this is an ancient and unfinished past, and can probably be unearthed only by listening to the stories of those who claim an inherited access to the region. Bombay, as we currently know it, begins in the 1800s, with the East India Company’s attempts to reclaim land from the sea, for reasons of profit and business. To this day, two centuries later, this construction plan has set the tone for the city. As the Urbs Prima in Indis, Bombay has almost entirely been seen as the city of dreams, in popular imagination — the arrival city, where the rural to urban migrant comes for better prospects.

In this article, I will explore how the Bandra Station incident,[i] the migrant exodus, and the everyday archives from Instagram (focusing on the posts of @thegreaterbombay) before and during the national lockdown have navigated the ‘flow of migrants.’ The lockdown is an event in this sense, it disrupts both the natural flow of the migrant population to Bombay, and the subjective ways of engaging with the urban space.

A defining image from the national lockdown, of what is now called the migrant exodus (from Bombay), is the Bandra Station incident that occurred on April 14, 2020. The social media spaces that concerned itself with the migrant crisis caused due to the lockdown, focused on the Mumbai Police’s lathi charge on the thousands of migrants that gathered at Bandra station, to critique how the urban space engaged with what they saw as an ‘unbelonging but necessary’ part of the city’s inhabitants (Phadke, Khan and Ranade 2011). This paper explores how the history of the migrant question crystallizes and breaks apart the image of Bombay as a city of and for the migrant in the Bandra Station incident.

2. Mumbaikar or Not: Who claims the city?

The natural flow of the migrant population has been assumed to be from rural areas across the country to the urban space offered by Bombay. A notable part of this, in the first few decades after the completion of Colaba Causeway in 1838, was from trade in opium and the city’s links with China – a past that it now pretends never happened. ‘Between 1830 and 1860, there was a tenfold increase in exports of narcotics through the city’s bustling port…though, as another historian contended, the city’s foundations actually lie in the opium plantations in Bihar’ (Fernandes 2013: 44).

What started off as the influx of tradable goods, soon became a route for the migrant labour’s entry into the city. Several communities claim the first place in this part of Bombay’s history – the Catholics who came with the Portuguese colonies, the Parsi and other Gujarati speaking trading communities, the ‘native’ Marathi speakers, and so on.

By the time of India’s independence, in 1947, Bombay was already a cosmopolitan space because of its diverse ethnic demography. The 1950s and the Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti (SMS), that was part of the larger demand for linguistic divisions to form political states within the country, was the first in a series of moves to ‘claim’ the Bombay identity on the basis of a geographic location or a language spoken (Windmiller 1956).

In the early 60s, with the formation of Maharashtra state with Bombay as its capital, the city witnessed its first consciously open questioning of who claims the Bombay identity. The Shiv Sena (SS), founded by Bal Thackeray, built on the demands of the SMS for making the ‘largely Marathi speaking’ Bombay as the capital of the state of Maharashtra (Purandare 2012).

When Bal Thackeray, a leading political cartoonist and the son of SMS leader Prabodhankar Thackeray, founded his party, he focused on the public discontent of having a linguistic state’s capital occupied by languages from outside the region. Most of the trade and industrial capital in the city were owned by the Gujarati speaking communities. Parallel to this was the large influx of South Indian immigrants who came to the city for the white-collar jobs that were available. Both these factors, the SS argued, were harmful to the native ‘Marathi Mhanoos’,[ii] who were losing out on the economic opportunities offered by an ‘inherently Maharashtrian’ space (Masselos 2007; Patel and Masselos 2003).

The SS organized protests, leading to the city shutting down, with narratives emerging of SS cadres vandalizing South Indian restaurants and pressurizing owners to hire Maharashtrian employees. How much of this was the SS capitalizing on the sentiments of a linguistic community over a perceived wrong cannot be analysed entirely due to the demography of the city. While it was the South Indian ‘job-takers’ who were restricted from claiming the ‘Bombay’ identity in the 60s, the question of who can claim the identity has been employed several times to draw attention to its diverse makeup, and its location as the capital city of a linguistic state.

The protests the city saw in the 70s and 80s had more to do with the changing economy and its repercussions on the city – the shutting of the textile, the massive unionization and protests organized by the mill workers, the SS’s attempts to play the linguistic card while generating employment opportunities – all coincided to form a turbulent two decades, until 1993, and the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

The 70s and 80s Bombay also saw the influx of the North Indian immigrants, who eventually were employed in either blue collar jobs, or by the film industry. With major players in the quickly solidifying space of Bollywood of the 50s-60s coming from the Hindi speaking belt, Bombay became the city of dreams, and synonymous with the country’s largest (and incidentally Hindi speaking) film industry (Gangnar 2003).

In 1993, with the demolition of Babri Masjid and the open alliance of the now ‘extremist Hindutva wadi’ SS with the BJP at the national stage (Masselos 2007: 363-385), the new unbelonger became the Muslim population. It was probably only incidental that the majority of the Muslim speaking people in the city, by this time at least, were migrants in some sense of the term.

Almost 40 years after the anti-South Indian protests that led to the rise of SS, the Sena split over internal differences. The Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS), led by Bal Thackeray’s nephew Raj Thackeray, also took an ostensibly anti-immigrant stance to forward its claims of ‘reconstructing Maharashtra’. In 2008, the party led widely controversial attacks against North India immigrants of the city. MNS, however, justified its violence on the grounds that the North Indian immigrants’ arrogance and refusal to assimilate to the city’s Marathi culture was a show of arrogance and a form of cultural bullying (Gaikwad 2008; ‘Sons of the Soil’ 2008).

A large part of Bombay’s history, post-Independence, has been written by these skirmishes between who claim the Mumbaikar identity, especially by the Marathi mhanoos, or the immigrants who keep the city running. In this context, the Bandra incident sees a movement in the opposite direction. With the lockdown came a shattering of the dreams that Bombay offered the immigrants, specifically those immigrants who had to stay in blue collar or temporary jobs. Here, state forces, incidentally backed by the incumbent SS government, strove to keep the migrants within the city, instead of attempting to resolve historical conflicts within the city that sought to keep them out.

3. The Migrant Identity

The forced lockdown in 2020 brought the city to a halt, a phenomenon that is contradictory to every popular myth — of the maximum city, the arrival city, and the city that never sleeps — that Bombay had generated. If we assume that the Bombay identity belongs to an individual who lives and works in that particular urban space, the lockdown essentially closed off the flow of ‘produce’, in terms of labour as well as goods, to the city. The unavailability of labour brings into focus the affordability question of who can access the city.

While a major part of the debates concerning legitimacy and the Bombay identity has been around the question of linguistic or regional belonging, I argue that one narrative of the migrant-run city must always be claimed by the workers who migrate there. The aspirations of the rural migrant – to get a job in the city and claim the urban identity – is also one aspect of this question. For the immigrant, this identity is tied to their survival and their economic aspirations. The claim to the Bombay identity is often enforced through the second generation of immigrants who settled in the (sub)urban space of Bombay, where the first generation of immigrants largely settled for blue collar jobs.

For example, there are several studies on the unique makeup of Dharavi, a slum that grew around such an immigrant settlement, and how the undocumented, unofficial labour of the slum, which contributes to the running of the city as a whole, is at odds with Bombay’s own claims of aspiring to be a first world city (Campana 2015). To the migrants, their primary claim to the Bombay space and thereby the Bombay identity, is through their work-focused engagement with the space.

There are two points that need to be examined when one considers the migrant narrative of the Bombay space. The first is how the migrant perceives their urban identity in relation to a space with which their primary mode of engagement is labour. The second is how a certain demography of the city perceives the migrant.

3.1. Access to Privacy, Access to Identity

Space, specifically private space, becomes a sought-after commodity and resource in the urban context. In a city like Bombay, where negotiations of space are already complicated by the limited availability, the ease of access to private space can transcend into a certain perception of the degree of an individual’s claims to the Bombay identity.

Bombay is the most populated urban space in the country. In direct opposition to this are the state sanctioned access and infrastructure provided for housing (access to private space). A 2011 Conference on Rental Housing specifies the following criterion for eligibility to claim a low-rent, state provided space:

“1. The allottee under the project shall have employment / self employment business within MMR and minimum family income of the allottee shall be Rs. 5000/- per month.

2. The allottee and his family member shall not own any house in Mumbai Metropolitan Region.

3. The allottee shall be continuously residing in the State of Maharashtra for at least 15 years before the date of application for rental housing. (as per modification in respect of rental housing DCR for MMR dated 04/06/09)” (Deshpande 2011)

The imagination of who gets to access private space itself is exclusionary, from the perspective of the lived reality of the migrant labourer in relation to the urban administrative authority. The disconnect between the demand for access to private space, and the methods of providing it, is because the ‘concerned authorities’ seem to be stubbornly holding on to a sense of permanence in the individual’s access to the urban space. The nature of labour that is accessible to the bulk of immigrants to Bombay, however, are erratic, and therefore, without a sense of permanence (Pendse 1995).

It is also interesting that this discussion is not limited to Bombay ‘proper’, i.e., the authorities that are concerned with the housing issue is one that governs the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR) comprising of 2 full and 3 partial districts, as opposed to the Mumbai City region which falls under the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). While the 2011 Rental Housing Authority (RHA) notes the lack of access to private space in the MMR, the BMC census results, published in the same year, records a drop in both the population within its region, and the number of working people in the Bombay space.

The larger question that this context brings is about the inherent connections between the access to private space in “Bombay”, which now extends beyond the exclusively ‘urban’ Town,[iii] and the people who can claim the Bombay identity.

3.2. Unbelongers

In Why Loiter?, the authors, while conducting a research project on women, risk and access to public space in Bombay, posit a category they term the “unbelonger”. While the study focuses on how every non-upper caste, non-upper/middle class, non-Hindu male in the public space of the city is, at some level, an unbelonger, it raises an important category of who is more easily perceived as such.

‘In Mumbai today, the unbelongers are the poor, cast in the role of ungracious migrants who occupy the city’s spatial assets without officially recorded remuneration; the dalits and other lower castes whose presence is barley acknowledged, except grudgingly on Ambedkar Jayanti; and the Muslims, who are increasingly stereotyped as disagreeable outsiders, criminals and potential terrorists. Then there are the couples we don’t wasn’t sullying our park benches, the non-vegetarians we don’t want residing in our building complexes, the bhaiyas we don’t want selling our fish or driving our cabs, the gays and lesbians we don’t want corrupting our young,, the North-Easterners we’d rather dismiss as ‘Nepali’, the elderly folk we don’t want occupying expensive real estate, the differently abled we’d rather just ignore than allow any access to public space in the city, and of course, in public space, all women without legitimate purpose, who should in any case be at home as good wives and mothers’ (Phadke, Khan and Ranade 2011).

While Why Loiter? focuses on the gender aspect of who occupies the public space in Bombay, I argue that the narrative of the unbelonging migrant is a combination of two narratives: 1) the unbelonging migrant’s own lack of access to private space, and 2) the perceiver’s narrative of this individual occupying a public space they see as rightfully belonging to them. This mythical perceiver can either be the administrative authority that allots private space on the basis of the longevity of an individual’s unbroken occupation of the Bombay space, or an individual in the city who imagines certain kinds of claims to the Bombay identity as inherently valid on the grounds of a particular kind of labour, an economic class, or a linguistic, regional or community identity.

4. The Kaali-Peeli: A Public-Private Space

It is in the context of this struggle to access private space and the Bombay identity that the kaali-peelis — the black and yellow metered taxis — embody this aspect of the Bombay narrative.

The kaali-peeli can be seen as a form of hired private transport that exists within the organized structures of public transport in Bombay. The structural organization of the kaali-peeli can be traced to the workers unions systems, which included the Taxi and Auto Drivers’ Union, in Bombay. In effect, because of the structure and the space that the kaali-peeli belongs to, the space within the vehicle can be seen as a moving private space within the public space of Bombay.

In a city that is constantly labelled as expensive and unaffordable, taking a kaali-peeli has often been perceived as a sign of luxury, which in turn implies that the passenger does not have to perform the labour of navigating Bombay’s streets. In other words, while taking the ride, the passenger is ‘not working Mainstream media representations of the kaali-peeli in Bombay have reinforced this idea – the cinematic representation of the kaali-peeli has been one that afforded the on-screen characters a sense of privacy and intimacy in the background of a bustling city. The kaali-peeli, in itself, stands in direct contrast to the bustle and hurry of the image of Bombay as the economic capital of India.

This narrative, however, needs a closer examination. The space of luxury and privacy that the kaali-peeli allows access to, is both placed between the passenger’s precarious work-based engagements with the city, while the taxi itself is a work space for the driver. The kaali-peeli is a paradox; it offers a tenuous access to privacy in an urban space where privacy itself is rarely available, and within this private space it is a constant negotiation between being the workspace of the driver and the non-work space of the other occupant(s).

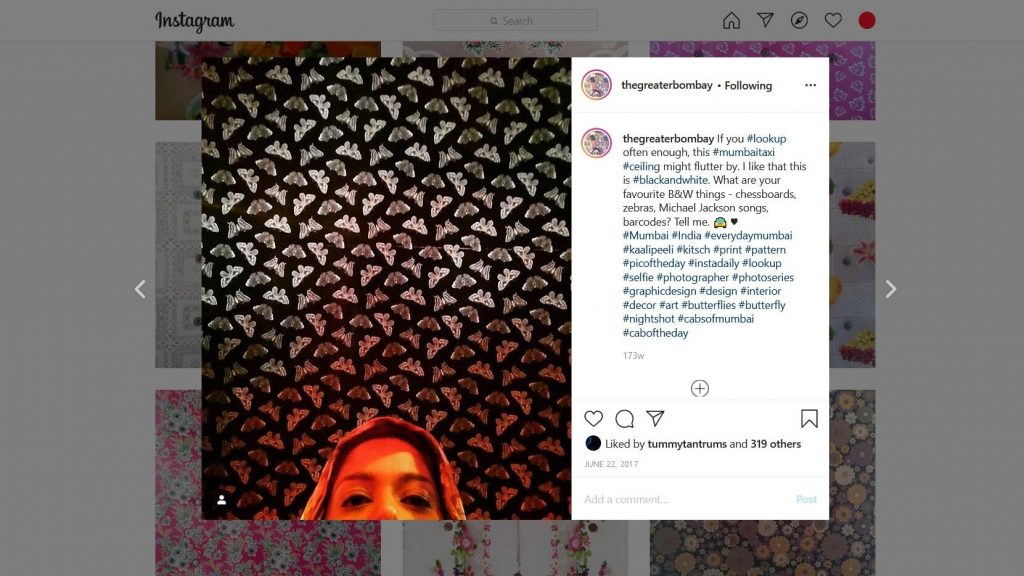

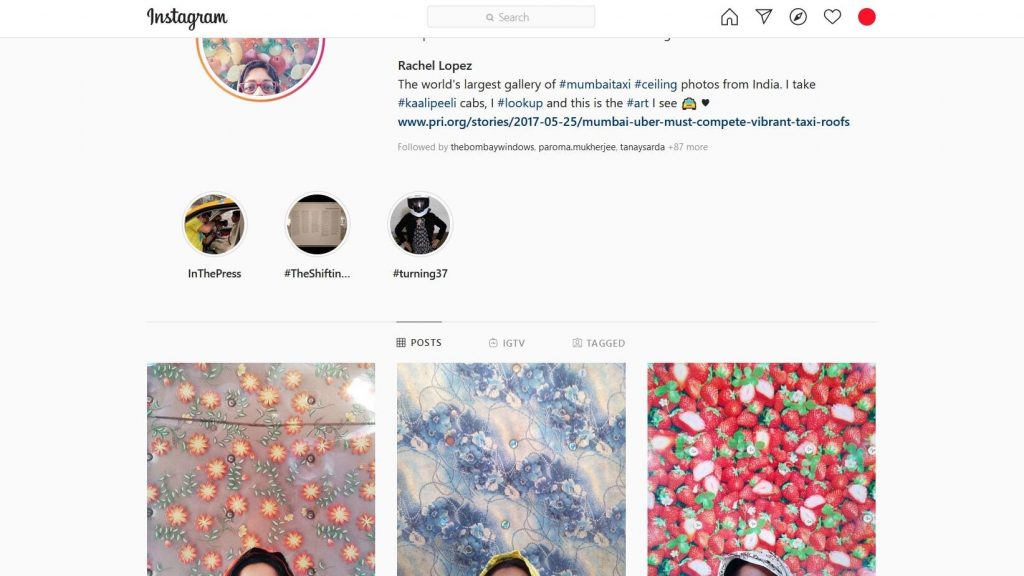

@thegreaterbombay’s Instagram handle is an archive that captures this paradox. While the user themself uses the taxi as a means to efficiently navigate work or other commitments within the Town (@thegreaterbombay 2018), the photographs are an act of ‘indulgence’ that can only be afforded by the passenger who has the time and economic resources to #lookup.[iv]The user describes their handle as the ‘world’s largest gallery of #mumbaitaxi #ceiling photos from India’. This paradox is also representative of the Bombay identity, especially for the migrant who is engaged in the sporadically available, blue-collar jobs including being a taxi driver.

[i] On April 14, 2020 a large gathering of what was widely reported as ‘migrant labourers’ were apprehended by the Mumbai Police at the Bandra Station. While individual reports vary on the nature and sequence of events, the general reporting on the incident agrees that the thousands gathered at the railway station staged a protest by defying the lockdown regulations, leading to lathi charge by the police. State officials later claimed that the gathering, and the events that followed, were caused due to a misinformation regarding the starting of the special trains arranged by the government to help long distance travels to the ‘poor’ and ‘migrant’ populations to their native regions.

[ii] This translates to the ‘Maharashtrian’ or ‘Marathi-speaking’ man’.

[iii] In Bombay (sub)urban slang, ‘Town’ (or SoBo, as is more popular among the younger immigrant population) refers to the South Bombay region extending from Colaba to Sion-Bandra. These were the original city limits, and they still comprise of the 9 wards under the BMC. What is referred to as Bombay, since the 1970s, has largely been the Bombay suburban districts, with the exclusion of neighbouring districts. As of now, the MMR consists of 5 districts (3 partially): Mumbai, Mumbai Suburban, Thane, Raigad and Palghar, extending the imagination of what passes off as ‘Mumbai’ or Bombay in the public imagination.

[iv] #lookup is a consistent hashtag used by @thegreaterbombay as a means to encourage their audience, specifically an audience that are accessing the kaali-peeli, to look up at the art they have captured in their personal experience of this space.

FIGURE 4.1

The rhetoric of @thegreaterbombay’s narration of the kaali-peeli is rather interesting. The image consists of the pattern on the taxi ceiling, interrupted by a part of the photographer’s face in the lower half. It is almost like a wary person peeking from under the frame into the camera. The focus of the camera is on the taxi ceiling itself, which presents a variety of patterns to the audience. In the image given here, the pattern is that of silvery-white butterflies embossed on a black background. Most of these photos, as the instagrammer remarks, ‘are in the bad lighting of a passing street lamp or while held at a traffic signal. It is the only point when the ride is steady enough for me to do this’ (@thegreaterbombay 2017). The act of producing the image itself becomes a narrative that embodies the paradox that is the kaali-peeli — the privacy of taking a partial selfie is in conflict with the traffic negotiations offered by the public roads of the city.

This negotiation between the public and private within the kaali-peeli also raises a secondary question – how do we interpret this negotiation and narrative in a kaali-peeli without passenger(s)? While the kaali-peeli still remains the workspace of the driver, a kaali-peeli without a passenger, by the mere virtue of being the kaali-peeli, must be seen as a private space. In this way, the driver can now be understood as occupying a private space. For the migrant who is also the driver, this offers a very specific kind of access to privacy in Bombay – one that is only provided by the workspace itself. This image is thus representative of the migrant narrative of Bombay, where the migrant identity intersects with the Bombay identity.

The migrant’s primary mode of engaging with the Bombay space is through work – Bombay is more of a work space, than a space where the idea of ‘leisure’ can be included in the concept of living in or occupying the space. The unbelonging migrant gains legitimacy to occupy this space, and claim the Bombay identity, by ‘working’. The kaali-peeli, because it is a paradoxical space of the public-private negotiations, thus becomes a microcosm of the larger Bombay narrative of accessing private space within the city, and thereby claiming the Bombay identity.

4.1. The Disappearance of the Kaali-Peeli

FIGURE 4.2

A second aspect of the narrative presented by @thegreaterbombay focuses on the kaali-peeli occupying the Bombay space itself. In 2020, Bombay’s last kaali-peeli Premier Padmini was decommissioned, following the municipality rules that demanded the deregistration of taxis over 20 years (Bhote 2020).

Since 1975, the Premier Padmini has been synonymous with the kaali-peelis, dominating the streets until the late 1990s. In the 2000s, with the deregistration rules coming in effect, these cars were forced to concede space to newer models and cars. The sheer longevity of the Premier Padmini in Bombay’s public space has been enough to make it an image synonymous with, and immediately evoking the space of Bombay. The film and photographic representations of this specific car as the kaali-peeli has been constantly in circulation, with the taxi driver as the protagonist of Taxi Taxie (1977) and Gaman (1978), and the taxi itself as the protagonist in the 2006 Taxi No. 9211.[i]

@thegreaterbombay’s images, specifically where the camera is placed in relation to its exclusive focus on the taxi ceiling, is almost like looking up from inside a coffin. The image is claustrophobia-inducing, clearly taken in a boxed-in space, with the only possible vantage being to turn upward. The photographer is also only partially present – a silent, wary observer witnessing a death-like framing brightened by instances of unintentional art.

The rhetoric of this framing is an ominous forewarning of the departure of a transport culture unique to and synonymous with Bombay. @thegreaterbombay’s archiving starts in April 2017, when there are around 50,000 kaali-peelis on the road, with only half of them being the iconic Padminis. By 2021, the number of kaali-peelis had fallen to less than 20,000; and much of their numbers were also replaced by the fleet taxis under corporate cab services, such as Uber or Ola. The world’s largest (and only) gallery of Mumbai taxi ceiling is simultaneously a frantic archiving of an image of the city that is being eroded through state intervention and time. The black and yellow has been replaced by plain whites, and the ceiling art and personal touches by the muted grey interiors of the new form of the taxi.

Parallel to this, is the context of migrant populations in Bombay reducing in number. While the intra-state migrant numbers were shown to have increased in the 2011 census, the inter-state migration to Bombay seems to have fallen (Shaikh 2019). The majority of the migrant population in Bombay is from the state of Uttar Pradesh, and this is the specific linguistic group that was targeted by the MNS in 2008-2009. Whether the repeated, increasingly aggressive anti-migrant sentiments is the reason behind this, or the general unaffordability of the Bombay space, the arrival city is no longer seeing the influx of migrants that it is accustomed to.

The popular imagination of Bombay as the destination city is being eroded. The Bombay of migrants is fading away, much as the kaali-peelis that are slowly disappearing from the city streets. The migrant narrative of Bombay is one that is made of a wishful sense of belonging to the Bombay identity, complicated by linguistic claims of precedence, exclusivity in the form of state regulations, and the inability to access a private space. The disappearance of the kaali-peeli seems to be indicative of the larger disappearance of a certain demography that contributed to a large amount of the popular image that Bombay generates. It is in this context of disappearance and the history of pushing away that the 2020 national lockdown, and the ‘Bandra incident’ occurs.

5. Bandra Station

On April 14, 2020, the central government announced an extension of the lockdown that was implemented in the country to control the Covid-19 pandemic. In Bombay, by the evening of the same day, thousands of people, described as migrant labourers, gathered at Bandra Station from where long-distance trains to other parts of the country could be accessed. Since March 23 of that year, the lockdown had been reported to have affected the livelihood of migrant labour across the country. In urban spaces, where migrants had no permanent or valid residence, an exodus-like move was reported, with the labourers choosing to sometimes walk back thousands of kilometres to reach home. A year later, there is still no official, state-provided data on how much damage to livelihood or impact on migration data this incident has caused.

In Bandra, the Mumbai Police was reported to have used force, resorting to lathi charge, to disperse the large crowds that had gathered “in defiance of the lockdown rules” (NDTV 2020). While reports of State Police forces using brutality on migrant movement was not isolated to this incident, in the context of Bombay’s migrant story, this becomes a deviation from the norm.

As we have seen above, Bombay’s migrant story is one of rejection and pushing out, starting with the muting of its history in opium trade, perhaps. Migrants have always come to Bombay and claimed the identity, despite linguistic and regional politics. Mainstream media and non-poor occupants of the city have seen the migrant situation in Bombay as a ‘problem’ that needs to be sorted or cleared by the relevant administrative authorities. Even with moves like the Slum Development Authority’s low-rent housing, the migrants’ access to owning or even renting private space in Bombay is limited. The policies surrounding legal access to such spaces are exclusionary, and the alternate solution to that — like the slums that have sprung up in different parts of the Mumbai city and suburban districts — have been presented as an aesthetic and security problem.

It is in this historical narrative of state agencies maintaining a stance that pushed out migrant workers, which the Bandra incident occurs. Here, in complete contrast to their earlier policies, the state forces were seen using their power to ensure that the migrants stay – to restrict the outflow of the migrant labour.

The paradox in the Bandra incident, specifically when seen in this historical context, is how the migrant’s perceived identity as the unbelonger remains constant. Whether the Bombay space, and here space implies the other identities and powers working in the city, pushes them out or tries to restrain them, the migrant’s access to both public and private space is problematic for the perceiver. They are unbelongers in the full sense of the term. The lack of a permanently validated economic reason to be in the Bombay space makes them undesirable add-ons to the city’s infrastructure, to the perceiver. Their attempts to access a private space in the city is subject to administrative gate keeping, and any attempt at an alternative solution must therefore be seen as suspect to the city’s ‘well-being’. This is the migrant narrative of Bombay.

To the migrant, then, it is only the work equation that can give them a sense of belonging, or even access to privacy in the Bombay space. The kaali-peeli is as much the identity of the migrant (driver), as it is their validation to claim the Bombay identity.

6. Conclusion

In this paper, I have attempted to suggest a method of taking disparate markers of popular imaginations of a space, like Bombay, and examine the narrative patterns that emerge within this context. The central figure, and the focal point of this narrative is the migrant. The Bombay space and the Bombay identity are only ever visible to us through the disparate images and imaginations of the migrant who is both an outsider and an insider to this geo-political space. The images themselves are taken from popular references and what is easily available in the public domain – the kaali-peeli that is synonymous with the city space, an Instagram handle that is documenting taxi ceiling art, census findings, and a sense of the movement of anti-migrant sentiments within the post-independence history of Bombay.

The purpose of this paper is to look at Bombay as a narrative product of the migrant and the city.

The image of the Bandra Station incident explored in this paper lies at the intersection of the long history of the right to access the Bombay space, and the conflicting identities that emerge from the political claims to the space. It can be argued that the majority of Bombay’s history is a history of urban migration in India. The SS’s and the MNS’s claims to the inherent Marathiness of the space has always been challenged by this migrant history. Within the popular imagination of the Bombay space the kaali-peeli have represented this conflicted claims to the Bombay identity. The passing of the kaali-peeli, documented by @thegreaterbombay, and the general history of the self-proclaimed ‘native’ claimants of the space pushing out the migrant ‘outsider’ run parallel to each other. The Bandra incident plays out in a direction opposite this historical narrative. At the point of the pandemic, when the migrant worker wanted to leave Bombay, the state (incidentally under SS) seemed to reverse its stance and refused to allow them to leave. It is this moment of disruption of the migrant narrative and experience of Bombay that this paper attempts to capture.

This paper analyses the image of the taxi ceiling in the dual context of the migrants contested claims to Bombay and Bombay’s history of assigning them the role of the unbelonger. To present a more rounded context to this narrative these disparate images have been examined using narrative studies as the methodology. All these images are results of lived experiences and therefore lived narratives of the Bombay space.

The advantage that methods of narrative studies, and specifically of considering verifiable data itself as a narrative, is that one can analyse the ‘story’ that emerges through tools offered by fictional rhetoric. Where data may fail to be updated or be impossible to access in a verifiable and consolidated form, the narrative logic of placing certain factors around a focal point can highlight patterns with which to analyse a situation.

A space like Instagram, where the subjective form of storytelling intersects with and is heavily influenced by an algorithm-based visibility and verifiability offers a respite when there is a lack of accessible data to archive a certain part of the city structure, like the migrant question in Bombay. In my attempts at accessing state-provided data, like the census, for instance, most analysis results and other consolidated, accessible forms were only available at a time much later than the moment when the actual data was a verifiable existence. Within the theoretical context of fictionality, this time lapse itself makes this ‘verifiable data’ fictional. For instance, the last census was in 2011, and its analysis results anywhere between then and 2014-15; at the time of writing this paper it is 2021. The data from the last accessible data is most likely to be drastically changed from the ground reality now. Therefore, because of the passage of time from the collection of data and its various published interpretations, these available data themselves take on a fictional quality. A mode of documenting the city, or one aspect of it, like @thegreaterbombay’s personal nostalgia for kaali-peelis spurring a social media gallery that exclusively archives kaali-peeli ceilings, allows for an alternate method of looking at the narrative aspects of available-vs-accessible data.

This method of reading narrative, that is exclusive to literature methodology, can help fill in the gaps of understanding in questions raised by discourse like urban studies, where the lack of updated or accessible data can pose difficulties. The narrative method also offers the possibility of a more empathetic engagement with the field, and with the lives of the people and spaces that make up these numbers. Further research into the applications of narrative analysis can potentially benefit both the literary and social science-oriented discourses.

Works Cited

@thegreaterbombay. 2016. ‘Hello butterfly covered #mumbaitaxi #ceiling!’, Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/BxHSBCFJVGu/?utm_medium=copy_link (accessed on 3 October 2021).

@thegreaterbombay. August 2017. Interview with Paravathy Rajendran.

@thegreaterbombay. January 2018. Interview with Paravathy Rajendran.

@thegreaterbombay. 2021. ‘thegreaterbombay’, Instagram, https://instagram.com/thegreaterbombay?utm_medium=copy_link (accessed on 3 October 2021).

Bhote, Karl. 2020. August 8, ‘Meter Down for the Last Time for Mumbai’s Iconic Kaali Peeli Fiat Taxi’, The Wire, https://thewire.in/culture/mumbai-taxi-fiat-padmini-bombay-kaali-peeli-taxi (accessed on 7 October 2021).

Cadell, Patrick, and John Page. 1958. ‘The Acquisition and Rise of Bombay’, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 3/4:113–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25202160 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

Campana, Joseph (ed). 2015. Dharavi: The City Within. Uttar Pradesh: Harper Collins.

Deshpande, S. C. 2011. ‘Presentation by Shri S. C. Deshpande to the Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation, Government of India Conference on Rental Housing’, National Research Estate Development Council, http://www.naredco.in/pdfs/sc-deshpande.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2021).

Fernandes, Naresh. 2013. City Adrift. New Delhi: Aleph Book Company.

Gaikwad, Rahi. 2008. Monday, October 20, ‘North Indians attacked in Mumbai’, The Hindu, https://web.archive.org/web/20081020131407/http://www.hindu.com/2008/10/20/stories/2008102057350100.htm (accessed on 29 September 2021).

Gangnar, Amrit. 2003. ‘Tinseltown: From Studios to Industry’, in Sujata Patel and Jim Masselos (eds), Bombay and Mumbai: The City in Transition, pp. 267-300, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Masselos, Jim. 2007. The City in Action: Bombay Struggles for Power. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Purandare, Vaibhav. 2012. Bal Thackeray and the Rise of Shiv Sena. Lotus Books.

Patel, Sujata and Jim Masselos. 2003. Bombay and Mumbai: The City in Transition. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Pendse, Sandeep. 1995. ‘Toil, Sweat and the City’ in Sujata Patel and Alice Thorner (eds), Bombay: Metaphor for Modern India, pp. 3-25. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Phadke, Shilpa, Sameera Khan, and Shilpi Ranade. 2011. Why Loiter? Women and Risk on Mumbai Streets. Penguin Books.

Shiakh, Zeeshan. 2019. July 28, ‘Explained: Here’s what Census data show about migrations to Mumbai’, The Indian Express, https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-heres-what-census-data-show-about-migrations-to-mumbai/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

‘Sons of the soil theory gets Supreme flak’. 2008. February 23, The Economic Times, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/sons-of-the-soil-theory-gets-supreme-flak/articleshow/2806197.cms (accessed on 29 September 2021).

NDTV. 2020. April 14, ‘Thousands Defy Lockdown At Bandra Station In Mumbai, Lathicharged By Cops’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8eAllJyyhQs (accessed on 15 September 2021).

Windmiller, Marshall. 1956. ‘The Politics of States Reorganization in India: The Case of Bombay’, Far Eastern Survey, 25(9): 129–143, https://doi.org/10.2307/3024387 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

Figure Captions

Figure 4.1. Example of post by @thegreaterbombay (@thegreaterbombay 2016).

@thegreaterbombay. 2021. ‘thegreaterbombay’, Instagram, https://instagram.com/thegreaterbombay?utm_medium=copy_link (accessed on 3 October 2021).

Figure 4.2. Screenshot of @thegreaterbombay’s Instagram wall (@thegreaterbombay 2021).

@thegreaterbombay. 2016. ‘Hello butterfly covered #mumbaitaxi #ceiling!’, Instagram, https://www.instagram.com/p/BxHSBCFJVGu/?utm_medium=copy_link (accessed on 3 October 2021).

[i] I am only citing the Hindi cinema references for two reasons. Hindi cinema has explored Bombay itself as a subject, while also engaging with Bombay as its production site for a major part of its history. Hindi cinema also becomes a primary source of reference for popular imaginations of Bombay that is immediately accessible to a large part of the Indian audience.

Acquainted myself with some facts about Mumbai which I didn’t know.