Abstract:-

The article in a conversational narrative describes the ecological credentials of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, and her friendship with Salim Ali, the naturalist and arguably India’s finest ornithologist. Drawing from the correspondence between the two, the article details the enormous influence that Ali had on the far-reaching decisions that Indira Gandhi took in regard to the protection of wildlife, forests and biospheres. Ali’s decisive interventions and intercedes, as the article recounts, convinced Indira Gandhi to sign the International Ramsar Convention in 1971 and later a treaty with the USSR for the protection of migratory birds. Known more for her political judgments and actions, many of which were criticized, the article uniquely brings out Indira Gandhi’s steadfast commitment to the environment even as several of her political and economic decisions floundered.

I

I am delighted to have been invited to speak at your college named after the mother of one of Mahatma Gandhi’s most ardent disciples who did much to keep his legacy alive. Some months ago, my good friend the eminent historian Nayanjot Lahiri spoke from this very podium and her lecture was entitled ‘A Prime Minister and an Archaeologist’. It revealed an unusual facet of India’s first Prime Minister and discussed the relationship between Jawaharlal Nehru and M.N. Deshpande. Inspired by that talk, I will speak today on ‘A Prime Minister and a Naturalist’ which is about Indira Gandhi and Salim Ali. For Indira Gandhi conserving India’s magnificent biodiversity was a daily obsession notwithstanding all the political and economic turbulence around her. India’s greatest ornithologist had much to do with helping her translate that passion in actions. They were ‘birds of the same feather’ when it came to matters relating to nature. You will appreciate the reason for this aviary description as I move along.

These days every political leader in the world wants to flaunt his or her environmental credentials but Indira Gandhi was a forceful ecological champion when it was not fashionable to be one. At the UN’s historic Paris Climate Change Summit in 2015, over 90 heads of state or government were present. How things have changed. Other than the host head of government, she was the only Prime Minister to address the very first UN Conference on the Human Environment at Stockholm in June 1972 and her speech there created a sensation instantly. It is widely considered a milestone in the global environmental discourse and is recalled even today. To her personal initiative and leadership we owe four laws that are still part of environmental governance—the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, the Water Pollution Control Act of 1974, the Forest Conservation Act of 1980 and the Air Pollution Control Act of 1981. To her abiding concerns we owe a number of successful species conservation programmes of which certainly Project Tiger is the most visible and talked about. The regulatory institutions we have like the ministries of environment and the pollution control boards trace their establishment back to her time.

More than being just a bird man, Salim Ali was a legendary naturalist best known for his association with the Bombay Natural History Society. His uncle was an early President of the Indian National Congress in the late nineteenth century and at least three other members of his extended family built great reputations as naturalists themselves– Humayun Abdulali, Zafar Futehally and Rauf Ali. Of these, the first two were also part of Indira Gandhi’s circle. Before 1947 Salim Ali had much to do with conservation activities in princely states like Bharatpur, Hyderabad and Mysore. He collaborated with Dillon Ripley of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC for over three decades and their jointly authored ten volumes on birds of the sub-continent remain standard reference works. Salim Ali’s autobiography The Fall of a Sparrow that was first published in 1985 has acquired the status of a classic.

Salim Ali’s prolific correspondence with Indira Gandhi has been carefully preserved in his archive at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library. Many of her replies too are contained in this collection. The National Archives also has much material relating the exchanges between them. I used both these and many other sources to write her environmental biography called Indira Gandhi: A Life in Nature which was published in 2017. Salim Ali naturally figures very prominently in it.

The far-reaching decisions that Indira Gandhi took particularly in regard to the protection of the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary in Rajasthan, the Chilka Lake in Orissa, the Silent Valley rain forest in the Western Ghats in Kerala and the sal forests in Bastar in what was then Madhya Pradesh were the direct outcome of Salim Ali’s entreaties and interventions. So was her entire approach to development of ecologically fragile areas like the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. He also played a decisive role in convincing Indira Gandhi that India should become a member of the Ramsar Convention on the protection of wetlands, Ramsar being the name of the Iranian city on the Caspian Sea where that international agreement was finalized in 1971. He persuaded Indira Gandhi to sign a treaty with the USSR for the protection of migratory birds. This finally happened in 1983 when she also wrote to the President of Pakistan and Prime Minister of Afghanistan to join India in a collaborative endeavour to protect the Siberian Cranes. A number of other conservationists wanting to alert and inform Indira Gandhi on some issue or the other would approach Salim Ali who would then intercede with the Prime Minister. Salim Ali was frank and forthright in all his interactions with her but she never took him amiss. She had full faith in his integrity and would always try and act on his advice. He would also bring the work of younger ecologists to her attention and she would invariably initiate action thereafter.

II

Indira Gandhi’s interest in nature was aroused, first and foremost, by her father. He introduced her to the world of books on nature and she became a voracious and wide-ranging reader. Her maternal uncle, a botanist and a collector of snakes kindled her curiosity for nature at a young age. Her mother’s illness meant that as a child and as a teenager Indira Gandhi spent considerable time in hill stations and developed a particular fondness for mountains. Her education first in Switzerland and later in Poona and more importantly in Shantiniketan further developed her communion with nature.

Indira Gandhi got to know of Salim Ali before she actually met him. Salim Ali writes that he met Nehru in Dehra Dun, where he had been jailed, and autographed his recently-released book called The Book of Indian Birds. This must have been between August 1941 when the book came out and December 3rd 1941 when Nehru left that prison.

The beginnings of Indira Gandhi’s direct connection with Salim Ali’s book is best recounted in her own words, contained in a foreword she wrote in 1959 to a book on Indian birds:

[…] Like most Indians I took birds for granted until my father sent me Dr. Salim Ali’s delightful book from Dehra Dun jail and opened my eyes to an entirely new world. Only then, did I realize how much I had been missing.

Bird watching is one of the most absorbing and rewarding activities. First, one learns to distinguish the different species, their nesting habits and their calls. Then gradually one realizes that birds are also little individuals each with his own characteristics.

[…] We are fortunate still to be able to live amongst birds even in our cities. In other countries you will have to go deep into the countryside to see any.

Twenty-three years later, at the centenary function of the Bombay Natural History Society in Bombay, she reminisced about Salim Ali’s classic yet again:

Dr. Salim Ali’s Book of Indian Birds and Prater’s Book of Indian Animals opened out a whole new world to many Indians. I had always loved animals. But I did not know much about birds until the high walls of Naini prison shut us off from them and for the first time I paid attention to bird songs. I noted the sounds and later on after my release my father sent me Dr. Salim Ali’s book and I was able to identify the birds from the book.

That Salim Ali had a pronounced influence on Indira Gandhi is proven by a letter she wrote to him on August 3rd 1980—this was in response to his note of condolence on the death of her younger son Sanjay:

I am grateful for your message of sympathy.

Sanjay was so full of fun and so vibrantly alive it is difficult to realize that he isn’t there any more.

You will have noticed that I am referring all issues concerned with ecology to you. I hope it is not too much of a burden and that you will help us to find amicable solutions. As you know, the State Governments are very persistent with their demands.

This was obviously no routine letter of acknowledgement.

III

Indira Gandhi was incarcerated from September 11th 1942 to May 13th 1943 in Naini Central Prison, Allahabad. It is here that she developed a life-long interest in bird-watching using Salim Ali’s book as a guide. In May 1950 she became one of the six founding members of the Delhi Bird Watching Society which had the Mahatma’s Quaker friend Horace Alexander as its President. Usha Ganguli joined in September 1950. She is widely acknowledged as having been one of India’s finest ornithologists but she died young in November 1970. Her husband, B. N. Ganguli, had been the vice chancellor of Delhi university and, in 1967, Indira Gandhi opened a school started by Usha Ganguli in the university campus which still runs. Ganguli’s A Guide to the Birds of the Delhi Area appeared posthumously in May 1975 with a foreword by Salim Ali and is the earliest authoritative work of its kind.

As I have mentioned earlier Salim Ali co-authored ten volumes with Dillon Ripley on the birds of the sub-continent. He would make it a point to send each of the volumes to Indira Gandhi. He sent the first of these sometime in late July 1968 and on August 3 1968 the Prime Minister sent him more than a perfunctory not of thanks:

I have not given up my interest in bird watching, so I was delighted to receive your new book. How thoughtful of you to send it to me.

News of this interest had travelled to Australia and New Zealand ahead of me and I was presented with two very lovely books there.

On May 12 1972 he sent the fifth volume which evoked this response from her five days later:

I am delighted to have your latest Handbook of Birds. Unfortunately, it is no longer possible for me to go on bird watching expeditions. I seem to be as great a curiosity as any bird to many watchers, including the security people! However, in my garden in Delhi and on tours I keep a sharp look out and it is surprising how many birds I do manage to spot sometimes even from an open jeep.

But Salim Ali’s association with Dillon Ripley would raise considerable controversy especially in Parliament. Remember this was the 1970s and talk on the CIA in India was common. The Prime Minister herself would every now and then allude to the American intelligence agency and its supposed activities in India. Relations with the USA had nosedived sharply after the stance President Nixon and Henry Kissinger had taken in 1971 over Pakistan’s military actions in what was then East Pakistan and what was very soon to become Bangladesh. American institutions were suspect and Dillon Ripley’s Smithsonian and its links with the Bombay Natural History Society came under scrutiny as well. Salim Ali was attacked particularly by MPs belonging the Communist parties.

As for Indira Gandhi, she remained unperturbed throughout the brouhaha surrounding Salim Ali. On November 16 1974, she released the tenth and final volume of the Salim Ali–Dillon Ripley handbook at her residence. It was as though she were telling Salim Ali’s critics—‘You shout what you want, but as far as I am concerned he is perfectly okay and continues to enjoy my friendship’.

The 1970s were also a period where it was almost impossible for American academics to get visas for study in India. But here again Indira Gandhi treated Salim Ali’s requests sympathetically. One beneficiary of Salim Ali’s intervention was a young primatologist called Steven Green who wanted to research the endangered lion-tailed macaques which numbered less than 200 in the southern most portions of the Western Ghats. As a result of the field research of Green and two of his colleagues the Kalakkad Reserve Forest was notified as a sanctuary for the lion-tailed macaque. Green left India in April 1975 and before leaving he sent a report to Salman Haidar the Prime Minister’s aide. He forwarded it to Indira Gandhi who after reading it queried:

Is he still in India? If in Delhi I should like to meet him.

Clearly impressed with Green’s analysis, on November 4 1975 she educated her senior colleague, Jagjivan Ram who was administratively in charge of forests and wildlife:

The attached report of the lion-tailed monkey of South India is alarming. This beautiful animal, found only in India, is rapidly approaching extinction. Large-scale habitat destruction and indiscriminate hunting have reduced its numbers to a dangerously low level.

The report also throws light on the decay of our forest wealth. As plantations take over from virgin forest and as forests continue to be over-exploited for revenues, far-reaching and potentially disastrous changes in the eco-system are taking place.

Urgent actions are needed for remedy this. The report pinpoints the Ashambu Hills as a crucial area to be preserved untouched […]

Please get in touch with the Chief Ministers of Tamil Nadu and Kerala and ask them to draw up concrete proposals […] This matter cannot be delayed.

IV

Indira Gandhi and Salim Ali would meet almost always in either her office or her residence in New Delhi. For the most part theirs was a friendship carried on through letters. But there were two unusual face-to-encounters.

In 1973, Indira Gandhi had made an exception a rule she adopted throughout her Prime Ministerial tenure and had become the patron of a non-governmental body—the Bombay Natural History Society. A year later on December 28th 1974 she spent about an hour at Hornbill House, the Society’s headquarters in Bombay. She was received by Salim Ali and others. There were no speeches and she spent her time looking at rare books and specimens, three of which attracted her special attention as a birdwatcher—Tickell’s flowerpecker which is the smallest bird in India; the monal pheasant, said to be the most beautiful bird found in the Himalayas; and the fulvous griffon vulture, one of the largest birds of prey.

On February 7 1976, Indira Gandhi went to the Bharatpur bird sanctuary along with her entire family—her two sons, their wives, and two grandchildren. Salim Ali, who had just been conferred with the Padma Vibhushan to add his Padma Bhushan of 1958, had already reached that venue.

The Prime Minister’s family and he went around the sanctuary lake by boat for about an hour, came back for breakfast and then went out again, returning a little before mid-day. They observed some sixty bird species. She spotted most of them using her own binoculars. Cranes came in for admiration on the boat drive—nearly 75 Siberian Cranes in the park then. Salim Ali explained about their ecology and outlined that these tall, all-white birds with a long red beak, were spread up to Bihar during early decades of the 20th century but their number had drastically declined. Reason, she asked. He said—loss of wetlands which were being drained or silted up. While leaving the forest lodge for a public meeting at Bharatpur, the prime minister wrote in the Visitor’s Book:

A delightful and peaceful experience made all the more enjoyable and interesting by having Dr. Salim Ali with us. I hope something will be done to close the lateral road, which brings buses and noise into the middle of the Sanctuary.

V

Salim Ali was indefatigable and advancing age did not seem to make any difference to his research. On May 27 1981 Dillon Ripley

wrote to the prime minister that Salim Ali and he wanted to travel to a ridge between Tirap and Lohit districts in Arunachal Pradesh. Ripley told her that that this area had never been visited by naturalist and was, a ‘treasure in India’s garland of natural wonders’. He was not above using some emotional blackmail—he said that Salim Ali was keen to accompany him and hoped that ‘it might be possible to visit this area before anything happens to our friend’. ‘Our friend’—that is Salim Ali, was eighty-five years old. Ripley himself was sixty-eight. When Ripley failed to receive a response from Indira Gandhi, he got Salim Ali to forward his letter to the prime minister a few weeks late which he did with this request:

Both Dr. Ripley and I are most anxious [to go the particular area] before it becomes too late (for me at any rate!).

Five days later, Indira Gandhi noted on Salim Ali’s letter:

I should very much like to oblige Shri Salim Ali for whom I have high regard. So far as I know, Dr. Ripley is reliable. But please look into the matter.

A flurry of correspondence followed involving the Intelligence Bureau, the Ministry of Home Affairs, the Department of Forests and Wildlife and the Department of Environment. The bureaucratic recommendation was that Ripley and Ali should be denied permission. But on July 12 1981 Indira Gandhi wrote to Salim Ali:

Last month you wrote for permission for you and Dr. S. Dillon Ripley to resume your field study of birds of the Namdapha area in Arunachal Pradesh’s Tirap district.

I am glad to say that all concerned Ministries have given their approval. The Ministry of Home Affairs will send you and the Arunachal Pradesh Government formal intimation of this decision.

Two years later the story would repeat itself. Indira Gandhi asked her officials to process yet another request from Salim Ali and Dillon Ripley visit Arunachal Pradesh. Again, all hell broke loose. This time though it was worse—for it wasn’t just the security and local administration but also the scientific bureaucracy that was opposed to the duo’s trip. Her own aide sent a long note of objections on March 31 1983 and against his observation that Salim Ali and Ripley had visited Arunachal Pradesh twice but no report had been submitted, Indira Gandhi noted:

Why not ask Dr. Salim Ali?

Further, against the aide’s observation that during the previous trip Ripley fired at an animal from a vehicle at dusk time, the prime minister noted:

I am sure this cannot be an ordinary gun. Various types of guns (which do not injure or kill) are used by scientists for scientific research.

Investigations continued and it was revealed that Ripley who had been charged with firing at a clouded leopard had actually shot at a civet cat.

It took almost four months for Ripley’s letter seeking permission to visit Arunachal Pradesh to be processed. In the end, permission was granted but as a concession to the nay-sayers the Prime Minister directed that ‘an official of the Wildlife Department should accompany them but not as a monitor of their activities’.

VI

Now and again, though, there were also some light-hearted moments in the correspondence between the prime minister and the ornithologist. On March 14 1979 Indira Gandhi wrote a delightfully chatty letter to Salim Ali—this was when she was out of power:

One day I found a typescript of your Azad Memorial Lecture on my table. I do not know who sent it but I was delighted to read it. The story of Maulana Saheb’s friendship with the sparrows reminded me of my father’s experience with the creatures in his barracks in various jails. An aunt of mine, now advanced in her 80s, has suddenly blossomed as a trade union leader. But she was the wife of an ICS officer and most of her life was spent in the districts. In Mainpuri or some such place, she got very annoyed with a sparrow who used to enter her room to peck at the looking glass. So she had it arrested and caged for a week or so as a punishment! I cannot now remember whether or not this cured the sparrow.

Here too we have a problem. Early mornings Sanjay has been scattering grains of bajra for the birds. Gradually more species were turning up. Our favourites were a growing family of partridges. However, since the last two months crows have decided to come, not to feed but to prevent the other birds. They rush at the smaller birds and clutch at the tails of the parrots and partridges. The result is that only the most intrepid birds now show up. The partridges who, as you know are over-cautious and have good reason to be, have deserted us and the number of other species has also decreased.

This was also the year in which Indira Gandhi began to get involved with Silent Valley—an evergreen rainforest in the Palakkad district of Kerala, in which a hydroelectric project was being planned. Her struggle to save it was the crowning achievement of her life as a conservationist. It all began when she was not Prime Minister and when she wrote to Salim Ali on October 2nd1979:

I have just received your letter of the 27th September. I share your concern about the Silent Valley and have been following the press campaign in favour of its preservation. I shall try my best to project your view to our party people but when the interests of conservation conflict with those of economic development, I am afraid it is not easy to persuade people to forego what they consider to be political and economic gain.

I should have been delighted to meet you but I am leaving Delhi tonight and will be back only on the 7th of October. If there is any special message you would like to convey to me could you please have it sent to one of my sons, Rajiv or Sanjay, who also love animals dearly and are deeply interested in conservation? At the moment, Rajiv is out on a flight but I am leaving a message with Sanjay.

Twelve days later she wrote to him again:

…When you saw me last you spoke of our including a passage on ecology in our manifesto. Some words have been put in but before we finalise the draft, it might be better for you to suggest the wording yourself. I cannot promise to accept it in its entirety but shall try to do my best. Could I please have this as soon as possible?

Salim Ali sent her a full page of formulations on October 26 1979 and the Congress’s manifesto for the Lok Sabha elections to held soon thereafter had a section called ‘ Ecology’ that declared:

The Congress-I feels deep concern at the indiscriminate and reckless felling of trees and the depletion of our forests and wild life, which upsets the ecological balance with recurring misery to the people and disastrous consequences for the country’s future. Projects which bring economic benefits must be so planned so as to preserve and enhance our natural wealth, our flora and fauna. In response to the economic and social necessity for ecological planning, the Congress-I will take effective steps—including setting up in the Government a specialized machinery with adequate powers—to ensure the prudent use of our land and marine resources by formulating clear policies in this regard for strict implementation.

That specialized machinery which the manifesto spoke about would come into being in November 1980 in the form of a full-fledged Department of Environment to which would added the subject of wildlife. Indira Gandhi would remain its Minister till her death.

On January 9 1980 when the election results had been declared and Indira Gandhi had thundered back to power, Salim Ali sent her an express telegram—the shortest communication he had with the Prime Minister. The telegram, which undoubtedly would have made Indira Gandhi smile, read thus: ‘Shabash (.) Am delighted.’

Their bonhomie is also evident in a letter from Salim Ali to Indira Gandhi January 15 1982 which also carried an interview of his in The Statesman. Salim Ali wittily described the interviewer Gopal Gandhi as a ‘double distilled’ grandson. Gopal Gandhi’s paternal grandfather was the Mahatma and his maternal grandfather was Rajaji. In the interview itself Salim Ali mentioned the fact that he had deliberately kept away from Jawaharlal Nehru—a leader he had known from the early 1940s— ‘lest it be suspected that I had axes to grind’. He added that ‘this was a tactical blunder because with his [Nehru’s] sympathetic backing much could have been done to conserve wildlife and forests’. He confessed that the error in judgment had made him wiser, and that he had found in Indira Gandhi ‘a knowledgeable bird watcher in her own right’ and an ecologist who, like her father, was deeply concerned about the environment.

There were informal exchanges as well. On August 8 1982, for instance, Indira Gandhi sent Salim Ali a clipping from The New York Times titled ‘Worldwide Tributes to the Beauties of Nature’. She wrote on the copy of the news-item: ‘Dr. Salim Ali may be interested in this’.The article mentioned four recent stamps in India that had been issued depicting unusual Himalayan flowers—blue poppy, showy inula, cobra lily and Brahma Kamal.

VII

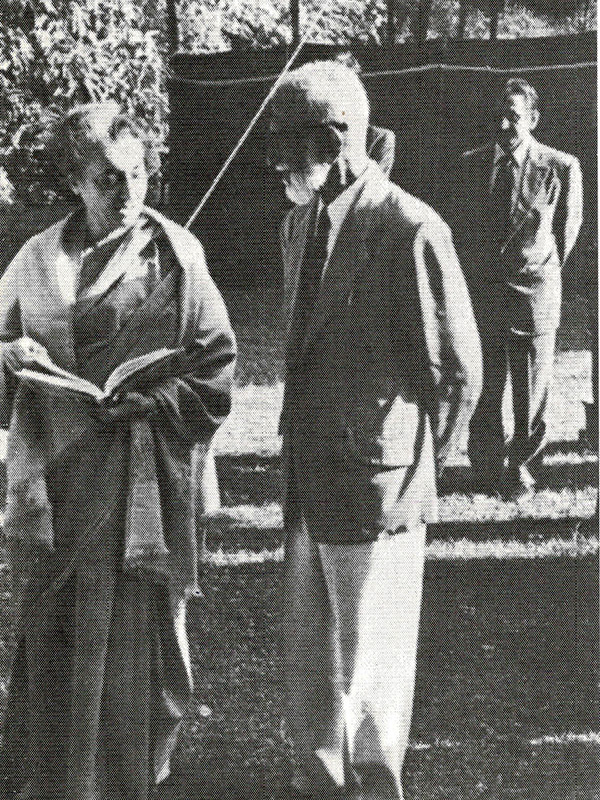

I have already mentioned Indira Gandhi’s visit to the BNHS on the occasion of its centenary. This is probably the last photo of her and Salim Ali together taken that day.

She was assassinated on October 31 1984. Just two days earlier she had finally fulfilled a life-long ambition—to see the chinar tree in Srinagar change its colours. Dillon Ripley, who had in two years earlier been chosen by Indira Gandhi as the co-chair of the Festival of India in America, came to Delhi as part of the official US delegation to Indira Gandhi’s funeral. He wrote to Salim Ali from the Maurya Sheraton where he was staying: ‘What a way to come to India! We are all so shocked and horrified’. Salim Ali replied eight days later in words that reflected his extreme anguish:

I was surprised to get a note from your Delhi hotel […] Though we were watching the whole dismal affair on TV all day, I did not notice anything that could be suspected to be you! I still find it hard to believe this dreadful catastrophe that has left us all stunned. It was the vilest and most despicable act of treachery one can imagine, and that it should have been perpetrated by her own security guards makes it more heinous and abominable […]

On January 2 1985 Salim Ali congratulated Rajiv Gandhi for his landslide electoral victory and went on to recall Indira Gandhi:

It was her deep personal concern for nature and environmental conservation that is responsible for whatever little we have been able to achieve in saving our fast vanishing wildlife and forests and we shall look to you to help in carrying on the good work patronized by her all through her stewardship of the country.

Subsequently on August 28 1985, the eighty-nine-year-old Salim Ali met the forty-one-year-old prime minister and wrote to him four days later:

I feel honoured at having being considered for nomination by you to the Rajya Sabha. As I tried to explain to you, my disqualifications for the responsibility at this stage of ‘senile decay’ are many and real. However, if you really feel that I may occasionally be of some help, especially in matters concerning environment and wildlife conservation I am willing to give myself a trial. It would give me the greatest satisfaction if I could be sure—as I was with your mother—that any environmental issue that I wished to bring to your attention would reach you directly and as quickly as possible [italics mine].

As a nominated member of Parliament Salim Ali continued his barrage of letters to the Prime Minister on various environmental issues. On March 9 1987 he wrote to Rajiv Gandhi to tell him that he was delighted that the latter had agreed to attend a seminar being organized thirty-five days hence in the nation’s capital on the BNHS’s research and conservation activities. On the morning of April 13 1987 Salim Ali fell ill and was hospitalized. But the seminar took place as scheduled and Rajiv Gandhi was present along with his family. He complimented Salim Ali handsomely and wished him a speedy recovery. Alas, two months later Salim Ali passed away. He was nine short of a century.

VIII

This morning I have narrated the story of an unusual friendship that in many ways shaped the environmental destiny of contemporary India. I have only given you a flavour of that jugalbandhi. The story is much deeper and richer than what I have been able to present in the time available. Indira Gandhi is both compelling and controversial. My purpose has been to awaken you to a relatively little-known aspect of this remarkable woman’s personality. In line with what our ancients taught us, she was convinced that ‘nature protects those who protect it’. In her determination to govern by this conviction Salim Ali was her confidant, sounding board and guide. At a time when India is confronted with the formidable challenge of sustaining ecological balance as it accelerates economic growth, this friendship and what it accomplished should be an inspiration to all of us. It is appropriate that I have delved into this subject a bit for Janki Devi’s great-granddaughter—Sunita Narain—has been for over three decades one of India’s most well-known environmental crusaders and conscience-keepers.

Suggested Reading

Ramesh, Jairam. 2017. Indira Gandhi: A Life in Nature. India: S&S India.

Ramesh, J. 2015. Green Signals: Ecology, Growth, and Democracy in India. India: OUP India.

Ali, S. 2007. The Fall of a Sparrow. India: OUP India.

Ali, S., Ripley, S. D., Dick, J. H. 1995. A Pictorial Guide to the Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. India: Bombay Natural History Society.

Dick, J. H., Daniel, J., Ali, S., Manakadan, R., Ripley, S. D., Bhopale, N. 2011. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent: A Field Guide. India: OUP India.

Whitaker, Z. 2017. Salim Mamoo and Me. India: Tulika Publishers.

Article by Shri. Jairam Ramesh